The Three C’s: Continuity, Contrast, Climax

Inside John Haynie's Studio: A Master Teacher's Lessons on Trumpet and Life

The word “musicianship” is used to describe a personal reaction to an experience of hearing music played or sung. Comments like “He plays with such feeling,” “She has such great style,” and “I could just hear the words when he played the song” are wonderful testaments to a meaningful performance. This could be equally true: “Even though he cracked a lot of notes, the overall performance was so musical.” What is the formula to develop musicianship?

Mark Hindsley was the Director of Bands at the University of Illinois and, by virtue of the fact that his wonderful daughter accepted my proposal for marriage in 1950, my father-in-law as well. He taught a course of band administration that covered many aspects of band performance. During one lecture, he talked about preparing a halftime performance for a football game and said, “Every performance must abide by the rule of the three C’s.” He went on to describe what these three C’s represented in the thought process: continuity, contrast, and climax.

I have never prepared a band for a halftime show, but I have incorporated the three C’s into the preparation of just about everything I played. More importantly, I often used the three C’s as a checklist in performances of my students.

Continuity is simply playing the correct notes and time, i.e., being able to play the music fluently. Developing an ability physically and mentally to play the trumpet is a never-ending responsibility and requires constant effort to develop and maintain technique. Embouchure, breath, tongue, and fingers are the elements from which continuity is made possible.

Contrast requires great imagination on the part of the player. Rarely does a composer write in all the nuances and dynamics he hopes will be played by the performer and expected by the listener. Some exaggeration must occur to transfer these dynamics and tempos to the audience. The fortes should be louder and the pianos should be softer. The allegros should be brisker and the adagios should be stretched. A great conductor once said, “When you think you have gone too far, it will be almost enough.” As a basic rule, make a crescendo when the melodic line ascends. As the line descends, get softer. For special times, do the opposite. Do not become too predictable. Keep the listener a little off-balance and wondering what is yet to come. The listener will pay more attention.

Climax is unique in that there should be a little climax here and a little there while preparing for the big one at the end. What if the music goes against the norm? How clever one would be to start right out with a strong climactic tone, then fading the ending. Of course, the music dictates the dynamics. Sometimes composers sprinkle in dynamic markings that have little relation to the notes they write. The musician in you will make the adjustments.

Some people will say that style and musicianship cannot be taught. It is true that some players instinctively do all the right things to make their playing enjoyable without instruction. I say that even these gifted players will benefit from additional help if some of their natural playing is contrary to what a particular piece of music needs and demands.

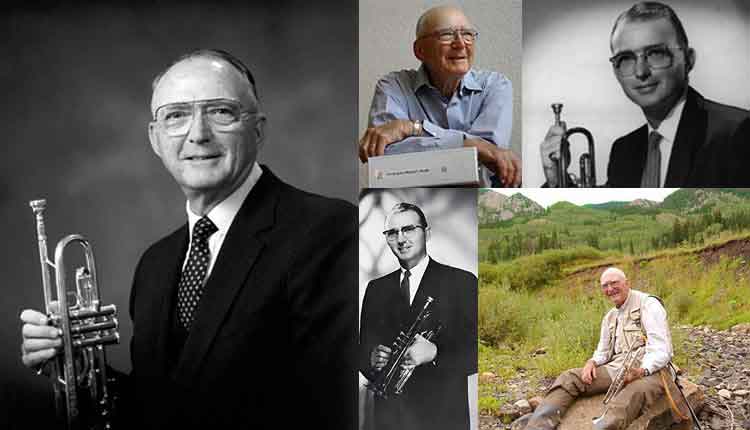

John and Marilyn, 1958